Every day about 80 funerals and memorial services are held on marae and in churches, temples, mosques, synagogues, funeral home chapels, community halls and suburban gardens around New Zealand. Death notices and obituaries (accounts of the life of the person who has died) are published in newspapers and on internet sites, or communicated by email.

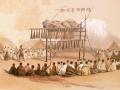

Tangihanga

Contemporary Māori practices for farewelling the dead continue traditions of tangihanga and usually take at least three days. Often the tūpāpaku (dead body) is brought back to the marae of their ancestors in an open casket or coffin. According to rules of different marae, the tūpāpaku is either placed in a separate house next to the wharenui, under the window on the veranda or against the back wall under the back post, or on the visitors’ side of the house. When a death occurs in the city and links with an ancestral marae are not strong, the body may come back to a suburban home, church or community hall.

The closest relatives of the person who has died – the bereaved family or whānau pani – have a particular role to play during the three-day tangi or set of rituals of farewell. They sit close to the tūpāpaku, who must not be left alone until they are buried. It is expected that whānau will show their emotions on the death of their family member. Family, friends and colleagues speak directly to the tūpāpaku (dead body). Songs and chants and traditional speeches are part of the rituals of tangihanga.

Mourners will accompany the body to the cemetery or urupā and Christian ritual is usually followed before the body is placed in the grave. Hands are washed when leaving the urupā to remove tapu (the sacredness of the place). The sharing of food after a burial brings everyone back into the world of the living and celebrates their connections.

Funerals and memorial services

Time spent with the dead body and close family and friends often precedes the formal funeral service. Contemporary funerals and memorial services are ways to farewell someone and also to shed tears and express grief together. The body is present at funerals, but not at memorial services. Committal ceremonies are also often performed at the graveside, before cremation or before burial at sea. Mourners usually share food and talk about the deceased at the end of funerals and memorial services.

Early settler funeral

When nine-year-old Barbara Macgregor died in the Matarawa valley near Whanganui in 1863, a short funeral address was offered in the family’s makeshift home. Later, the Reverend Richard Taylor (who recorded the event in his diary) read the 39th Psalm to about 60 people assembled outside the house and invited them to pray. Barbara’s coffin was placed in a spring cart and taken up hill where it was ‘simply let down into the grave and the earth thrown in without any further ceremony’.1

Funerals in the past were religious events and affirmed the spiritual beliefs of the participants. This changed in the late 20th century as fewer people identified with particular religious traditions.

While Pākehā women and children were often excluded from funerals in the late 19th and early 20th century, attitudes to their involvement in funerals shifted during the 20th century. Men, women and children have always participated in tangi.

In the early 21st century some funerals were entirely secular, while others combined secular music, poetry and speeches with religious ritual, texts and music.

Public funerals

Some funerals and memorial services were small gatherings of close family members, but other funerals involved whole communities, cities and nations or attracted international attention.

Public funerals for politicians, famous people or the victims of natural disasters draw crowds who may view the body, watch the funeral cortège or procession, and sometimes attend the funeral ceremony. State funerals such as those for former Prime Minister Peter Fraser (1950), Māori Queen Te Arikinui Dame Te Atairangikaahu (2006), and mountaineer Sir Edmund Hillary (2008) were photographed, filmed or televised, and attended by large numbers of people.

Cost of funerals

The cost of funerals, memorial services and cremation is usually met by family members. In the past, people could contribute to burial societies that covered their funeral expenses. In the 21st century some people pre-plan and pre-pay their funerals. Others may take out funeral insurance. Most people leave planning and paying to their executors. In 2018 funerals cost $8,000 to $10,000 on average.

Conducting the ceremony

In the past, religious figures such as priests, ministers and rabbis usually officiated at funerals. In the early 21st century a range of people conducted funerals and memorial services. Funeral directors often worked with religious leaders, professional celebrants, family members, friends and colleagues to organise death and funeral notices, funeral programmes, photo displays, transport, music, flowers, and food and drink after the ceremony.

Funeral directors also offer memorial websites on which mourners can record tributes to the person who has died.

Doing something different

Funeral celebrant Mary Hancock argues that people often want something different from standard religious services. She says, ‘the freedom we have to create new rituals and ceremonies … is part of what keeps on making New Zealand and its culture attractive to migrants’.2

Diverse ceremonies

Funeral and memorial services vary depending on religious beliefs, cultural practices, the age of the person and how they died.

The person conducting the ceremony welcomes the participants and tells them what will happen. Words, songs, chants, music and images are used to remember the person who has died and express what their life and death means for those participating.

At some point in the ceremony there will be a ritual of farewell. This could take the form of a prayer, chant or special blessing, the reading of a religious text, or the removal of the body by pall-bearers to a hearse (a special funeral vehicle) or to the graveside.

Post-funeral rituals

In many cultures it is important for mourners to share food after a funeral. Māori refer to this as te hākari or the post-tangi feast. Sometimes mourners offer food at a shrine, burn incense, or plant trees or shrubs. Prayers, chants and songs are seen as ways to assist the transition of the spirit from one form of being to another. In some traditions, after the burial the home is blessed or cleansed by sprinkling water.