He korero whakarapopoto

Children’s health

For much of the 20th century New Zealand led the world in child health. Infant mortality – a major health indicator – was the lowest in the world. But child and youth health in rich countries improved faster than in New Zealand, and in the early 21st century it had relatively high infant and child death rates and youth suicide rates compared to other Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries.

Children from the poorest families were much more likely to be hospitalised with diseases like rheumatic fever or bronchiectasis (a lung disease) than children from rich families. In 2013, 22% of Auckland children lived in crowded houses, and household crowding is linked to illnesses such as rheumatic fever, influenza, bronchiolitis and meningitis. In the early 21st century Māori and Pacific children were more likely to have to have poorer health outcomes and have specific health needs than other ethnic groups.

Diseases

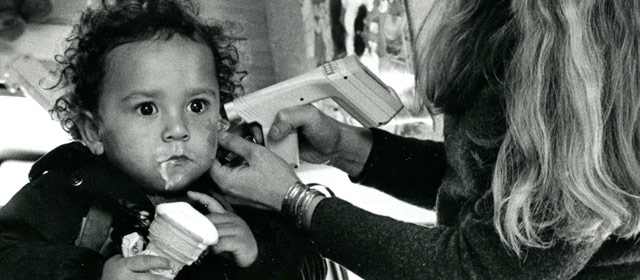

Diseases such as polio and tuberculosis (TB) affected children till the mid-20th century, when vaccines were developed to prevent them. In 2016 children could be vaccinated for free to prevent 12 diseases. However, New Zealand's rate of vaccination was lower than many other OECD countries.

Child health issues

In the 1980s New Zealand’s rate of cot death or sudden unexpected death in infancy (when a baby dies, often during sleep, and there is no explanation why) was high. A study found that babies whose parents smoked, who were put to sleep on their fronts or who were not breastfed had a higher chance of cot death or sudden unexpected death in infancy (SUDI). Babies living in poor housing with parents on very low incomes were more likely to experience cot death or SUDI.

The rate of SUDI dropped from 4 per 1,000 births in 1986 to 0.8 per 1,000 live births in 2014. The Māori rate was much higher – it also dropped, but in 2014 it was 1.7 per 1,000 live births. The rates for Pacific babies was lower at 0.8 per 1,000 live births, but higher than the rate for European/other babies (0.4 per 1,000 live births) and Asian babies (0.1 per 1,000 live births).

In 20017/18, 12% of children aged 2 to 14 years were obese. Rates were higher among Māori (17%) and Pacific children (30%). Obesity is associated with illnesses such as diabetes.

Between 15–20% of children had asthma in the 21st century, with much higher rates for Māori and Pacific children.

Youth health issues

Between 2002 and 2016, 36% of youth (15–24 years) deaths were due to suicide. Teenagers and young men were far more likely than young women to die as a result of suicide or in a car accident. Mortality rates among Māori and Pacific teenagers and young adults (15–24 years) are significantly higher than rates among non-Māori, non-Pacific young people. Mortality was also closely related to levels of material deprivation or inequality in the households of teenagers and young adults.

In 2015/16 almost 60% of young people aged 15 to 17 years had drunk alcohol in the past year but rates of consumption had decreased since 2006/7. Rates of smoking had also dropped – in 2015/16, 6% of young people smoked regularly, compared with 16% in 2006/7.

Primary health

Plunket was set up in 1907 to help parents to care for their babies. It provides free health and wellbeing services for children aged 0–5 through nurses who make home visits and provide support at clinics and through Plunket Line – a telephone advisory service for parents.

Many schools have a school nurse. Doctors in general practice are subsidised to provide free care for children under 13 years. From December 2018 free visits are available to those 13 years and under.

In 2018 there were seven health camps or children's villages for children with social and emotional problems, or who had experienced neglect or abuse.

There was only one specialist stand-alone children’s hospital, Starship Hospital in Auckland. Kidz First Hospital was established as part of Middlemore Hospital in 2000 and offered child and family hospital services to a culturally diverse South Auckland community. Other hospitals had children’s wards.