Story summary

Pre-European health

Māori were generally fit and healthy before Europeans came to New Zealand. Many illnesses common in other parts of the world were not found here. Diseases such as pneumonia, arthritis and rheumatism did affect Māori.

People believed they got sick because they had not obeyed rules about tapu, or had offended the gods. They sought healing from tohunga who knew about rongoā rākau (plant medicines) and which karakia to say.

European diseases

When Europeans arrived, diseases such as measles, influenza, typhoid fever and tuberculosis decimated local tribes who had no immunity to them. Māori who had limited contact with Europeans were less badly hit.

The Māori population fell by 10% to 30% between 1769 and 1840.

As more Europeans arrived, all tribes were affected by disease. The loss of their land through confiscation and sale left people with poor housing, dirty water supplies and an unhealthy diet. The Māori population probably halved from its 1840 level until it began to grow again in the 1890s. People developed immunity to diseases, and the government provided some medical care.

Māori health

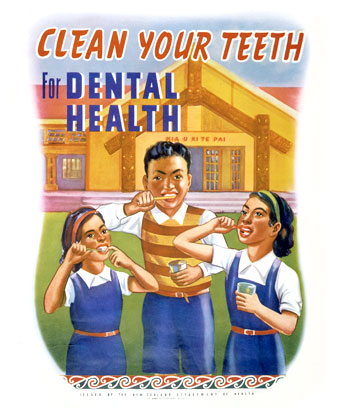

The Public Health Department was set up in 1900, with a Māori section. Native health officer Māui Pōmare travelled around the country giving advice on health to tribes. The Young Māori Party also pushed for better health for Māori.

Native health nurses treated people in rural areas.

But typhoid, smallpox and influenza still affected Māori badly. In the 1918 influenza epidemic the Māori death rate was more than eight times the Pākehā rate.

People still practised traditional health treatments, and in 1907 the Tohunga Suppression Act was passed to stop tohunga giving people harmful treatments. However, tohunga continued to practise.

Health improves

From the 1920s to the 1940s the Māori population increased rapidly.

In the 1930s the first study of Māori living conditions found that many people were living in poor, overcrowded houses, without clean water. In 1935 the Māori death rate from tuberculosis was 10 times the Pākehā rate. A scheme to build better houses for Māori began in 1935. There was a project to improve toilet facilities.

Until the 1920s most Māori mothers were helped by relatives when they gave birth. Nurses began attending births, and by 1937, 17% of Māori births took place in hospital.

In 1939 hospital treatment was made free, and more Māori went to hospital when sick, or to give birth.

Changing health

Deaths from tuberculosis and typhoid fever began to decline in the 1950s, but Māori were more affected by diabetes, cancer, heart disease and stroke. In 1960 the Māori mortality rate was twice the Pākehā rate.

In the 1980s Māori began to run their own health programmes, some involving traditional medicine.

In 2012–14, Māori life expectancy was less than Pākehā life expectancy – by 6.8 years for women and 7.3 years for men. Māori were worse off in terms of employment, income, education and housing, all factors in people’s health.