The pā harakeke

Aitia te wahine i roto i te pā harakeke.

Marry the woman found in the flax plantation.

This whakataukī (proverb) indicates the central importance of weaving and related crafts such as tukutuku in Māori society. The pā harakeke is a stand of flax, either specially cultivated or naturally occurring, which is cropped sustainably by weavers to provide the basic material for their work.

New materials for a cooler climate

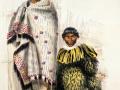

When the ancestors of modern Māori migrated to New Zealand from other Polynesian islands, they arrived in a land with a much cooler climate, and were forced to develop a number of cultural innovations. Warm clothing was needed, but the aute (paper mulberry), the plant used to make tapa-cloth garments elsewhere in the South Pacific, did not thrive in their new home.

In place of aute, early Māori developed a method of producing fine thread from muka (fibre), from which they wove garments and other items of extraordinary beauty.

Harakeke (Phormium spp., New Zealand flax, although in fact of the lily family and not botanically related to the European flax plant) was the main substitute for aute. It assumed enormous importance for its abundance and suitability for plaiting, weaving and other fibre techniques. Other plants used for weaving include kiekie, pīngao, kākaho (toetoe stems) and many more.

Types of flax

Harakeke (New Zealand flax) is found throughout the country, is strong and versatile, and has always been the most widely used plant material for traditional weaving. Over time, weavers selected and grew varieties with specific properties, such as extra white or glossy muka (fibre). These might be exchanged with tribes in other regions. Some of the names given to different varieties include pari-taniwha, oue, rātāroa, ngutu-nui, awanga, tāneāwai, ruatapu, tukura, rongotainui, motuoruhi and mangaeka.

Harvesting flax

The two main varieties of flax are harakeke (Phormium tenax) and wharariki (Phormium cookianum), which has softer leaves, prized for use in more delicate work. There are many identified sub-species, each with its own weaving properties and recognised uses.

Leaves (rau) for weaving were carefully cut from the flax bushes to ensure that te rito (the centre shoot) was not harmed. Several Māori proverbs liken the flax bush to a human family, which survives by protecting its weakest members.

Preparing muka

Each leaf was then stripped by hand to remove the edges and midrib, leaving even widths of the rau (harakeke leaf). An incision was made on the dull side of the harakeke, often using the straight edge of a shell to extract the muka. For use in soft, comfortable garments, the muka was thoroughly washed and beaten with a patu muka or patu whītau (stone pounder). Groups of individual fibres were carefully miro (hand-rolled), often against the leg, to produce the whenu (warp threads) and aho (weft threads). The aho was much smaller in width – about a sixth of the size of the whenu. The aho did not have to go through the patu process.

Weaving threads were traditionally dyed yellow, red-brown and black, with the natural colour of undyed fibre providing a fourth colour. The bark of trees such as the raurekau (Coprosma grandifolia) produced yellow dye. The tānekaha (Phyllocladus trichomanoides) produced a reddish colour, and when mixed with hot wood ashes produced a brown. To dye muka black, the bark of a plant such as the makomako (Aristotelia serrata) or hīnau (Elaeocarpus dentatus) was first steeped in water. The muka was soaked in this liquid, then dried and rubbed in a special paru (mud) found in swamps.

Te whare pora

Traditionally, a novice weaver was taught in a special building called te whare pora (the house of weaving). This instruction was given under strict conditions and with a great deal of ceremony. The novice was first made ready to receive knowledge of the arts of weaving through karakia (prayers) and initiation ceremonies. The karakia endowed the student with a receptive mind and retentive memory. Initiated weavers became dedicated to the pursuit of a complete knowledge of weaving, including the spiritual concepts. The practice was discouraged by 19th-century missionaries, and very few weavers in the present day experience this initiation ceremony.

Weaving was mainly, although not exclusively, practised by women. The principal goddess of te whare pora is Hineteiwaiwa, who represents the arts pursued by women and is also the goddess of childbirth.