Story summary

Whānau and hapū

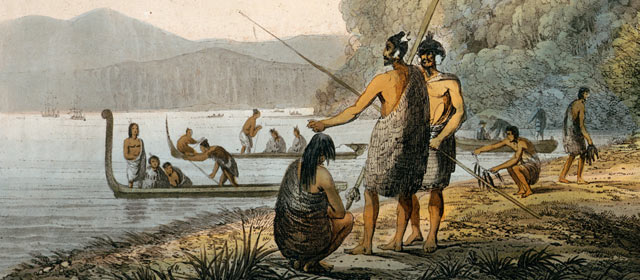

The economic activities of Māori were based on whānau and hapū. Many people lived in villages close to the shore with its fish and shellfish. Ideal spots had fresh water, land for gardens and a nearby forest for catching birds. Kūmara, taro and hue (gourds) were plants brought from Polynesia and grown in New Zealand. Kurī (dogs) and kiore (rats) were also introduced foods.

Goods were traded through gift exchanges – giving a gift created an obligation to return a gift.

Trade with Europeans

When Europeans arrived Māori exchanged gifts with them. This turned into a bartering economy. Tribes began growing potatoes and by 1805 these were traded in the Bay of Islands. Pigs and potatoes became important trading goods for tribes.

Whalers traded with locals and some Māori became whalers. Māori sailors brought back gifts from overseas. A flax trade grew up with Australia. Tribes purchased muskets and began to rely more on goods produced for trade.

Increased trade, 1840 to 1860

At first, new European settlements were dependent on Māori for food.

Māori invested in tools, flour mills and ships. They grew wheat and exported it to Sydney. In the late 1850s the price of wheat in Australia dropped by a half and tribes lost their market.

Land purchase and confiscation

The Crown bought millions of hectares of land in the South Island. By the 1860s almost the entire island was owned by the Crown or European settlers.

In the North Island tribes in the Wairarapa, Wellington and Manawatū sold much of their land. Tribes tried to stop the sale of land and tensions grew. Fighting broke out, and after the wars around 3 million acres (over 1.2 million hectares) of Māori land was confiscated.

Māori had to prove they owned land in the land court. Many people had to sell land to pay for the costs of court proceedings. Under the new laws, land was owned by those named on the land title, and individual people could not get loans to develop land.

Rural economy from the 1870s

Most Māori lived in rural areas and did manual work as farm labourers, shearers and gum diggers.

In the 1920s politician and Māori leader Apirana Ngata was able to get government money for Māori to develop their land.

Urbanisation

In the 1930s, 90% of the Māori population was rural. During the Second World War Māori were moved to cities to work in essential industries. Soldiers returning from the war often settled in cities.

In 1951, 40% of Māori men worked in agriculture, forestry, hunting and fishing. By 1971 only 13% worked in agriculture.

People in towns mostly did manual labour. Because Māori were educated to be farmers, most worked in low-skilled jobs.

Government reforms, 1980s

From 1985 tribes were able to take historic claims to the Waitangi Tribunal. Treaty of Waitangi settlements saw millions of dollars of land, assets and money returned to tribes, including fisheries and forests.

At the same time the government made big changes in the economy and many Māori lost their jobs. In 1992 New Zealand’s unemployment rate was 10% but Māori unemployment was 25%.

Māori economy, early 2000s

Treaty settlements have enabled tribes to grow businesses – in 2008 the total assets of Ngāi Tahu and Tainui were worth over a billion dollars. The total value of Māori land trusts and incorporations was estimated to be over $3 billion in 2005/6. Many more Māori owned their own businesses – in 2001, 17,100 Māori were self-employed.