Page 1: Biography

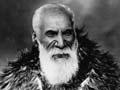

Tūroa, Tōpia Peehi

?–1903

Te Āti Haunui-a-Pāpārangi leader

This biography, written by Ian Church, was first published in the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography in 1993. It was translated into te reo Māori by the Dictionary of New Zealand Biography team.

Tōpia Peehi Tūroa was a chief of Ngāti Patutokotoko hapū of Te Āti Haunui-a-Pāpārangi of the upper Whanganui River. His influence extended to Lake Taupō. Born probably in the second decade of the nineteeth century, he was known in his youth as Te Mutumutu. His father was Te Peehi Pakoro Tūroa and his grandfather was Te Peehi Tūroa. He traced his descent from Whanganui lines and from Turi of Aotea; he was also descended from Tākitimu, Te Arawa and Tainui ancestors. His mother's name may have been Utaora.

Tōpia Peehi Tūroa was engaged throughout his life in a series of conflicts, in which it seems his principal aim was to assert his authority and that of his tribe within the Māori world. However, he also recognised the importance of Māori unity to counter the threat posed by European law and culture. The tension between these aspirations is illustrated in the events of his life.

He grew up in the turbulent era of the musket wars, and was involved in fighting when his father opposed the sale of land for Whanganui township in 1847. He married Makarena Ngārewa, daughter of Te Kahuti and Te Rangi. Two of their children, Wiari Hōhepa and Hīpirini, were baptised by Father P. J. Viard of the Catholic mission in September 1857; on 14 November 1858 Tūroa and his wife accepted baptism from Father Jean Lampila, and in April 1860 another child, Ateraita, was baptised by Father J. E. Pezant. Tūroa took the name Tōpia (Tobias) at baptism. There were at least two other children, Makarena and Kiingi Tōpia.

Tūroa emerged as a man of resolve and an influential leader. When Tāmihana Te Rauparaha mooted the idea of a Māori king in 1854 it is said that he had Tūroa in mind; other sources say that Mātene Te Whiwhi put his name forward. Although Tūroa declined in favour of Iwikau Te Heuheu he believed that unity under a king would enable Māori to retain both land and mana. At Pūkawa in November 1856 he was again offered the kingship, but he signalled his support of Pōtatau Te Wherowhero's nomination by receiving Waikato emissaries in 1857. He led 60 men from Ōhinemutu, near Pipiriki, in June 1858 to show allegiance to King Pōtatau.

It is likely that Tūroa was with the Whanganui contingent at Pēria in October 1862 when the King movement discussed its attitude to the Waitara dispute, and again at Tātaraimaka in 1863. He told the Reverend Richard Taylor that the Taranaki quarrel involved all Māori and that their mana was at stake. The outcome was that his people became adherents of Pai Mārire in May 1864. They were defeated at the battle of Ōhoutahi in February 1865, where Tōpia Tūroa was wounded. He met Governor George Grey on 15 March but, unlike his father, refused to take the oath of allegiance. Grey believed that he was implicated in the killings of James Hewett and the Reverend C. S. Völkner and (after giving him a day to get away) declared him outlawed with a reward of £1,000 for his capture.

In April 1865 Pipiriki was garrisoned by colonial troops. Tūroa regarded this as a challenge and responded by assembling some 1,000 Whanganui, Ngāti Pēhi, Ngāti Tūwharetoa and Ngāti Raukawa at Pukehīnau and Ōhinemutu. They besieged Pipiriki for 12 days from 19 July, withdrawing beyond Ōhinemutu when government reinforcements arrived. One consequence was the exclusion of Tōpia Tūroa's father from Grey's general pardon of October 1865.

From his bases near Pipiriki Tūroa hoped to reclaim the Whanganui coast. However, the majority of the Taupō people opted to live peaceably, while retaining their Hauhau beliefs. Only Tōpia Tūroa and eight others vowed to carry on to the death. Responding to the warning of his relative Takuira that if Ngāti Pēhi followed Tūroa they would 'see the men in boots marching round this lake [Taupō] in less than a month', Tūroa exclaimed 'I and my people will never submit to the Pākehā; we will never make peace with the Governor. No; never! never!!'

In 1868 the King movement declined to support Tītokowaru: Rewi Maniapoto sent word that Tūroa was the only recognised spokesman for the Whanganui tribes. Tūroa, however, remained aloof from the King movement, with which he had become disillusioned. He felt that he had been wrong to submit his mana to unworthy Waikato chiefs. Te Kooti's killing of a relative near Lake Taupō in September 1869 provided the opportunity to reassert the mana of Whanganui. By taking this opportunity, Tūroa transferred his allegiance from the King movement to the colonial government. He agreed to bring 200 men and join Te Keepa Te Rangihiwinui (Major Kemp) in the pursuit of Te Kooti after Te Keepa's success at Te Pōrere in October 1869.

In November, at Ōhinemutu and Rānana, Tūroa discussed several issues with William Fox, including the grievance over the imprisonment of Ngāwaka Taurua and his Pakakohe people at Dunedin. Fox, however, refused to agree to their release. As a symbol of unity with the lower Whanganui people Tūroa had an effigy of Hōri Kīngi Te Ānaua carved on the centre pole of his new house, Te Ao Mārama, at Ōhinemutu. Fox, to show the government's confidence in him, presented Tūroa with 40 Enfield rifles and ammunition. Te Keepa's force, with Tūroa nominally in charge, set off at the end of December to locate Te Kooti.

The village of Tāpapa was taken on 24 January 1870 but Te Kooti escaped and the chase continued into the broken Mamaku range where scouting was difficult. In the Bay of Plenty Tūroa's force was based at Ōhiwa and made forays into the Urewera country. Tūroa became a major in the New Zealand Militia, Native Contingent. He and Te Keepa were paid £15,000 for the service of their men and Tūroa received a pension of £200 a year.

After the capture of Waipuna pā and 100 of Te Kooti's followers in the Waiōeka Gorge in March 1870, the Whanganui force returned to Ōpōtiki. It has been said Tūroa refused to hand over the prisoners to Te Keepa for execution. In April he and his men were shipped home to Whanganui.

In April 1872 Tūroa welcomed Governor George Bowen to Tokaanu saying: 'Men and land have been the cause of my troubles – Tāwhiao and the boundaries of our land. I was a stray sheep that went astray, and more joy was shown at my return than for the ninety-and-nine that had remained in the fold.' While he praised the government's generosity Tūroa warned Bowen that he looked upon Taupō 'with a jealous eye.'

The issue of land claims remained unresolved. Tūroa tried unsuccessfully to persuade Te Whiti-o-Rongomai to seek redress for his grievances through the courts. But the government's failure to address the problem finally led Tūroa to renew his covenant with King Tāwhiao, and in 1884 he accompanied him to London. Although they met Lord Derby, their petition to Queen Victoria was simply referred back to the New Zealand government. After Tāwhiao's party returned to New Zealand Tūroa and Hōri Rōpiha convened a meeting at Poutū (near Lake Rotoaira) attended by a thousand people from the area. Tūroa introduced resolutions to acknowledge King Tāwhiao, to acknowledge Queen Victoria but not the colonial government, to withdraw from the Native Land Court, and to stop surveys, sales, or leases of land. He also proposed that the people should abstain from voting for the Māori representatives in Parliament and set up their own committees under Tāwhiao to run local affairs. The meeting decided to resist the construction of the main trunk railway by declining to work or by demanding high prices for timber.

Major David Scannell, resident magistrate of Taupō, in his report to the government in 1886 offered the opinion that Tūroa was annoyed because his pension had been stopped when he went to England. He suggested that Tūroa was too cautious to act openly. The impact of the meeting was weakened because some invited chiefs, including Tāwhiao, did not attend, and, as Scannell observed cynically, because some of the signatories to the resolutions were 'the first to apply to pass their lands through the Court.'

Tūroa's influence in the southern Taupō region waned. In 1886 his claims to Mt Ruapehu were regarded as secondary to those of Ngāti Tūwharetoa. The following year Tōpine Te Mamaku, chief of Ngāti Hāuaterangi from the upper Whanganui, died, whereupon Tūroa became paramount chief of the Whanganui tribes; from this time he took less part in Taupō affairs. He chaired a meeting at Koriniti in September 1889 when the development of the Whanganui River to allow steamers to reach Taumarunui was discussed. The local people agreed not to hinder works provided that their eel weirs were protected. However, there was trouble between them and the contractors in 1892 and 1893. In March 1894, Richard Seddon, minister for public works and native minister, and James Carroll, member of the Executive Council representing the native race, went to Tieke to discuss the problem with Tōpia Tūroa. They struck a deal by which it was agreed to establish a township and school at Pipiriki.

In his final years Tūroa seems to have come to terms with the conflict of interests which had beset him. His relationship with the government remained amicable. At some stage his pension was restored and in June 1901 he attended the Māori welcome to the duke and duchess of Cornwall and of York at Rotorua. He moved down the river to Kūkuta, then to Aramoho, where he died on 26 October 1903.