RUA | 2

1769–1835 New contact and new words

Key events in this chapter

- 1769–1779: James Cook notices the similarity of Polynesian languages and makes the first known attempt to record Māori words in writing

- 1814: On Christmas Day, Ruatara interprets Samuel Marsden’s sermon in te reo Māori

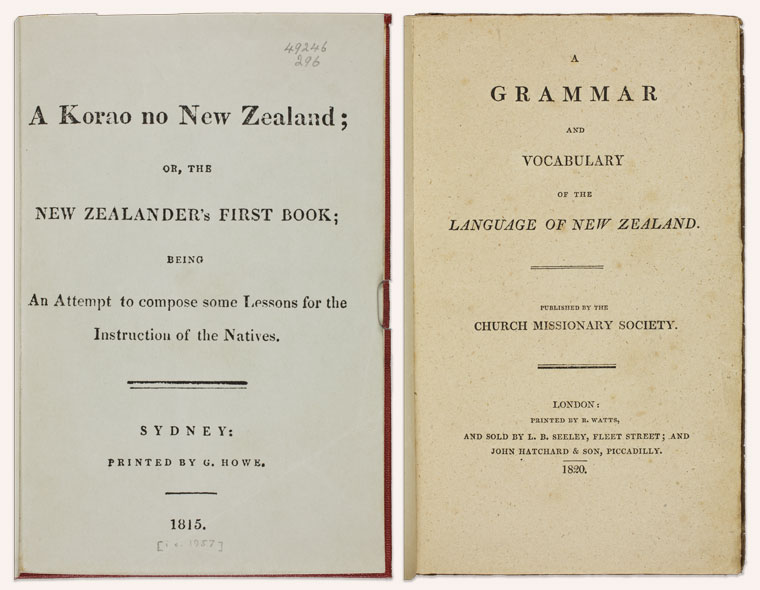

- 1820: A Grammar and vocabulary of the language of New Zealand, compiled by Thomas Kendall, is published. This lays the orthographic foundations of written Māori

- 1827: With the help of missionaries William and Henry Williams, the first scriptures in Māori are published in Sydney

From 1769, Māori began to interact with new visitors to their lands. At first, it was European men under the guise of exploration, then whalers and sealers from Europe and North America, and later missionaries. They brought with them different languages, technologies and ideas, all of which Māori adopted when it suited them to do so.

British Library; Reference: ADD MS 15508, Folio 12

During the early period of contact between Māori and Europeans, Māori was the predominant language of New Zealand. It was used extensively in social, religious, commercial and political interactions among Māori, and between Māori and Pākehā.

It is easy to recognise the use of new technology when it is attached to physical objects. As Māori incorporated new foodstuffs, tools and weapons into their lives, they adapted previous Māori words. The various words for musket often started with ‘pū’, a prefix for wind instruments: pūkaea, pūtātara, pūtōrino. In other cases, foreign words were transliterated – mīere (‘miel’ is the French word for honey), parāoa (flour/bread) and pepa (paper).

Much more complicated was the adoption of religion. Missionaries were among the earliest European arrivals. One of the first formal religious orations was given in 1814, when Ngāpuhi leader Ruatara translated Samuel Marsden’s Christmas service, including a sermon based on Luke 2:10 (the birth of Jesus). Two years later, the first mission school opened at Hohi (Oihi) in the Bay of Islands, with both Māori and Pākehā pupils.

Missionaries soon learnt te reo Māori in order to (they hoped) spread the good news about Christianity. There is certainly evidence that Māori engaged with concepts in the Bible, seeing correlations between genealogies and whakapapa, parables and kupu whakarite, and prayers and karakia. There was also a perception that Christianity was one of the advantageous technologies Europeans had brought with them, and therefore worth adopting.

Alexander Turnbull Library; Reference: B-077-002. Lithograph by Jack Morgan

What is certain is that Māori took to literacy with speed and enthusiasm. Reading and writing were intrinsically linked to religion, as missionaries taught Māori to read and write and Māori in turn taught missionaries more about te reo Māori.

Alexander Turnbull Library; Reference: B-K-1049-COVER (left); B-K-2-TITLE (right)

As te reo Māori had never been written down before, an orthography (conventions for how a language is written) needed to be created. The first attempt at this was a collaboration between two Ngāpuhi rangatira, Hongi Hika and Waikato, and Thomas Kendall, a missionary stationed at Rangihoua. In 1820, they travelled to Cambridge, England to work with Professor Samuel Lee. The result was the Grammar and vocabulary of the language of New Zealand.

Alexander Turnbull Library; Reference: G-618; Oil painting by James Barry

Back in Aotearoa, Māori were learning to read and write at an astonishing rate. Literacy became another new skill that could increase mana – northern rangatira boasted that their children could read and write. Missionary translators and printers struggled to keep up with the demand for printed texts, most of which were religious in nature.

The different groups of European arrivals picked up te reo Māori in various ways. The missionaries actively learnt the language; their children absorbed it as they grew up surrounded by Māori. Some whalers and sealers married Māori women or worked with Māori communities, and by necessity acquired a working knowledge of te reo Māori.

In the first half of the 19th century, te reo Māori was still the primary medium of conversation, although some Māori became bilingual before the 1840s.

For the teacher

Te Mana o te Reo Māori is great for students' self-directed learning. They can explore the chapters in their own time and at their own pace.

Support them with specially created educational resources that focus on exploring their own personal connections to te reo Māori.

These resources develop the students' understanding of Whakapapa, Tūrangawaewae, Whanaungatanga, Mana Motuhake, and Kaitiakitanga though key questions, activities, and language support.