WHITU | 7

The WAI11 claim

Key events in this chapter

- 1975: The Treaty of Waitangi Act is passed and the Waitangi Tribunal established

- Early 1985: Te Reo Māori claim (WAI11) is lodged with the Waitangi Tribunal by Ngā Kaiwhakapūmau i te Reo

- 24–28 June 1985: WAI11 hearing takes place at Waiwhetū Marae

- 29 April 1986: Report of the Waitangi Tribunal on Te Reo Māori Claim (WAI11) is published

- 1987: Māori Language Act makes te reo Māori an official language of New Zealand.

In the 1970s, Māori campaigning opened up a new avenue for change: the Waitangi Tribunal. Initiated by Labour Cabinet minister Matiu Rata, the Tribunal was established as an independent body to investigate alleged breaches of the Treaty of Waitangi by the Crown. When it was set up in 1975, the Tribunal could only investigate contemporary breaches, those that had happened since its establishment. (This was later changed to allow claims dating back to 1840 to be heard.) By 1984 only a few claims had been investigated and these were related to specific iwi/hapū and locations. In 1984, Nga Kaiwhakapūmau i te Reo – the organisation behind the first Māori radio station – and one of its founders, Huirangi Waikerepuru, lodged a claim that affected all Māori. Allocated the ID ‘WAI11’ (as the 11th claim lodged), it would become known as ‘The Te Reo Maori Claim’ and have a large impact on the revitalisation of te reo Māori.

The Hearing

After a claim is lodged with the Tribunal, research is carried out and a hearing is held. Tribunal hearings are similar to, but not quite the same as, ordinary court hearings. Evidence is presented by the claimants (in this case Huirangi Waikerepuru and Nga Kaiwhakapūmau i te Reo) and their expert witnesses. The Crown, as the defendant, can also present evidence and call expert witnesses. Representing the Tribunal in the WAI11 claim were panel members Eddie Durie (Presiding Officer), Graham Latimer and Paul Temm.

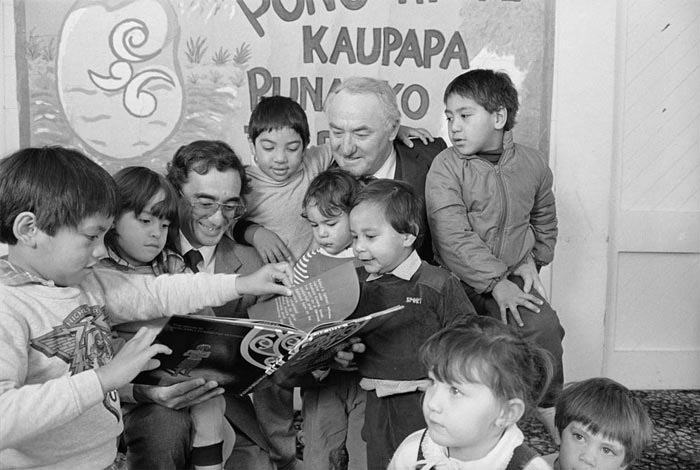

Alexander Turnbull Library, Dominion Post Collection (PAColl-7327); Reference: EP/1985/2942/15-F. Photograph by John Nicholson

In 1985 the claimants and their supporters, the Crown and their representatives, and the panel members and Tribunal staff gathered at Waiwhetū Marae in Lower Hutt for four weeks of hearings (considered a very long hearing at the time). Supporting the claimants were Māori from all over Aotearoa, from kaumātua who had seen the language gradually lost, to young activists who were fighting for its survival. The claimants argued that the Crown had contributed to the erosion and loss of language by excluding it from laws relating to education, health, broadcasting, and the Māori people. Government policies furthered this loss. These laws and policies prejudiced (had a negative impact on) the claimants, as te reo Māori was not part of everyday New Zealand society; it was not heard in important places like Parliament, courtrooms, government departments and hospitals. ‘Because of this lack of official recognition in legislation,’ the claimants stated, ‘the Māori language has no mana within all Government departments and public bodies.’ 1

Because the Crown signed Te Tiriti o Waitangi, the claimants reasoned, it had a responsibility to look after te reo Māori. The second article of Te Tiriti made several guarantees to Māori, including ‘o rātou taonga katoa’, translated by prominent Māori scholar Hirini Moko Mead as ‘all their valued customs and possessions’. 2 These included tangible items (like land) and intangible things (like culture). One of these taonga was the Māori language.

In signing Te Tiriti, the Crown had also promised under the third article to protect Māori. The claimants said this meant ‘active protection’. It was not enough to simply leave Māori to speak their own language; the Crown had to take steps to protect it. It had not done so and the language was being left to die.

The report, recommendations and results

After the hearings and following further research, the Tribunal released its findings in a report published in 1986. It agreed with the claimants that te reo Māori was a taonga that the Crown must actively protect. The report was critical of the Minister of Education’s policies and actions towards the language, and the hands-off approach the Crown had taken in broadcasting.

The report made five recommendations. Tribunal recommendations are generally not binding, and the Crown implemented these recommendations in varying degrees.

The first two recommendations were:

- That legislation be introduced so that anyone can use te reo Māori in any of New Zealand’s courts of law, government departments, local authorities and other public bodies.

- That an organisation be set up to supervise and foster the use and preservation of te reo Māori.

These recommendations were addressed in 1987. The Māori Language Act made te reo Māori an official language of New Zealand, which allowed the use of Māori in the courts, but didn’t extend to government departments. The Act also established Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori (the Māori Language Commission).

TVNZ

The remaining recommendations were:

- That an enquiry into the education of Māori children take place.

While such an enquiry was never held, the Education Amendment Act 1989 gave recognition to kura kaupapa and wānanga. This was a small step. An outstanding kaupapa inquiry on education services and outcomes is still to be heard by the Waitangi Tribunal.

- That broadcasting policy recognises and protects te reo Māori.

The implementation of this recommendation was complicated by the sale of state-owned broadcasting assets and significant restructuring of the sector. Ultimately, the Crown’s actions were seen as insufficient and further claims were brought to the Tribunal – WAI26 and WAI150.

TVNZ

- That employees of the public service become bilingual, if necessary to their job.

While some public servants today are bilingual, the majority are not. There are various initiatives in place to encourage public servants to become bilingual, but much work remains to achieve this goal. The long-term effects of any Tribunal report can sometimes be hard to discern, and WAI11 is no different. Speaking in 2016, Judge Joe Williams looked back on the hearing he had presented at as a junior law lecturer:

It’s wrong to think of the Tribunal here as an instigator; it's more that it was the voice … It translated Māori desires into a format that Government could understand and that the public could understand. And that’s the role that consistently played through those 80s. The rest was the Maori leaders taking out that momentum and dealing with it the way they will. 3

The Tribunal had helped give Māori a voice when speaking to the Crown about te reo Māori revitalisation. It was now time for the Crown to act.

For the teacher

Te Mana o te Reo Māori is great for students' self-directed learning. They can explore the chapters in their own time and at their own pace.

Support them with specially created educational resources that focus on exploring their own personal connections to te reo Māori.

These resources develop the students' understanding of Whakapapa, Tūrangawaewae, Whanaungatanga, Mana Motuhake, and Kaitiakitanga though key questions, activities, and language support.

1 Ngā Whakapūmau i te Reo Inc., quoted in Aaron Smale, ‘Te Tai – Te Reo Māori Treaty Settlement Stories – Te Reo Māori in Broadcasting’, Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori, Wellington, July 2018, p 9

2 Waitangi Tribunal, Report of the Waitangi Tribunal on the Te Reo Maori claim (WAI11), Wellington: 1993, p 22