Parliament and the Waitangi Tribunal

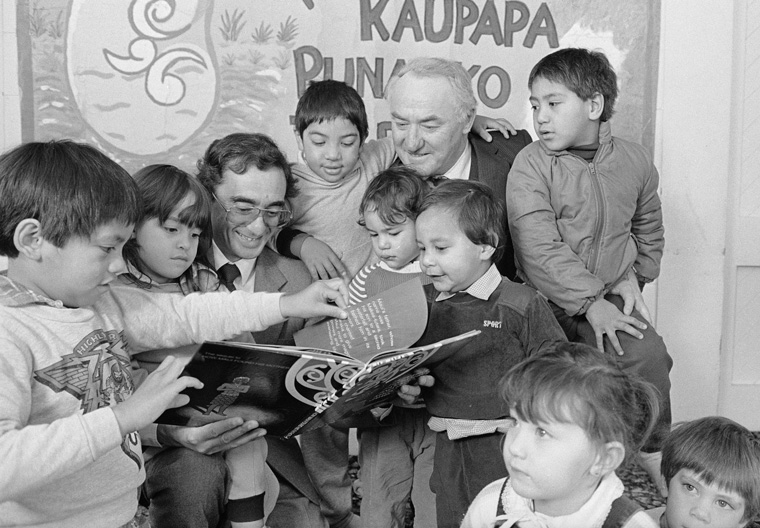

Alexander Turnbull Library; Reference: EP/1985/2942/15-F

To obtain official status and the associated recognition for te reo Māori, legislation was needed. Only Parliament can pass a law. New Zealand has no formal recognition of the Treaty of Waitangi as a founding document – or any other written constitution – so Parliament was, and is, where people go to seek change.

Ngā Tamatoa and the Te Reo Māori Society began the modern period of revitalisation efforts with the 1972 petition calling for official recognition of te reo Māori and its teaching in schools. Parliament did not legislate in response.

Three years later the Labour government, with Matiu Rata as Minister of Māori Affairs, established the Waitangi Tribunal as a permanent Commission of Inquiry able to make recommendations to the government. As Sir Douglas Graham, a later (National) Minister in Charge of Treaty Negotiations, put it, this gave Māori ‘at long last a place to air their grievances and not surprisingly they have seized the moment’.

The Tribunal was free to interpret the law and make findings and recommendations. When the te reo Māori (WAI11) claim came before it, it made full use of these powers. Much further legislation followed, including the Māori Language Act 1987, which became law 15 years after the te reo Māori petition was delivered to Parliament.